|

|

Tannis, Aspenden Inventory from 1569 |

|

|

|

Tannis, Aspenden Inventory from 1569 |

|

Tannis was a large country house in the Manor of Berkesdon in the parish of Aspenden and the following article is an account of the furnishings in 1569 as described in an inventory. Because of the size of the house (14 bedrooms are recorded) a significant variety of goods and chattels are listed - and as a result it gives a good idea of what people owned - and how it is described in contemporary documents. While the spelling may seem odd by today's standards it often makes sense if you try to read it out loud phonetically.

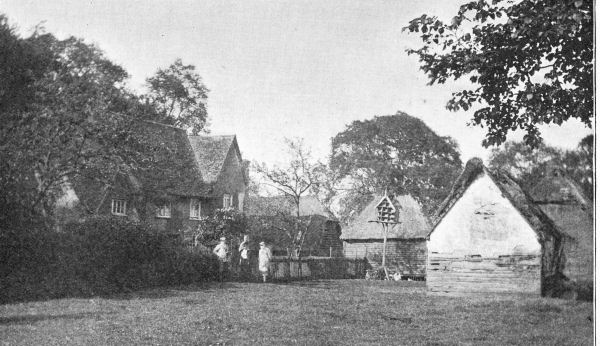

From Home Counties Magazine, Volume VI, p256-264, 1904 TANNIS. THE INVENTORY INDENTED OF HOUSEHOLD STUFF TAKEN THERE THE XXVI DAY OF JUNE IN THE ELEVENTH YERE OF THE REIGNE OF QUENE ELIZABETH ANNO DNI. 1569. By W. MINET, F.S.A. ACCOUNTS and statistics of all kinds are notoriously dull and uninteresting documents to those who have no personal concern in them, and an agent's list of the contents of a house may well be placed in the same category, yet let any one of these lie hidden for a sufficient time, it will be found to have gained a secondary interest far eclipsing its original value, an interest which increases in proportion to the time it has lain hidden. For reasons into which this is not the place to enquire, the daily life of our ancestors has for the most of us an abiding charm, and any document which enables us to reconstitute this has to-day a value out of all proportion to that which it may have possessed when first drawn up. I therefore make no excuse for printing what at the time was a mere formal list of the contents of Tannis House in 1569. Tannis stood in the parish of Aspenden, not far from Buntingford, in Hertfordshire. A farm called Tannis Court still exists, but the house of 1569 is more probably that represented in the illustration, about a quarter of a mile away and surrounded, as were so many Hertfordshire houses, by a still existing moat. The inventory is signed by Edward Halfehide, and sealed with his seal, having in base, two chevrons conjoined, and in chief three seeded roses; the chevrons we know to have been the then recently acquired blazon of the family, but the origin of the roses is still to seek.1 We may fairly assume that the furniture was the property of Halfehide, and the house may have been his also, though this point is far from clear. Chauncy, speaking of the manor of Barkesdon in which Tannis would seem to be situated, says that Andrew Judd sold a portion of the manor to Edward Halfe hide, then possessor of Tannis, who settled it on his wife for her jointure. He goes on to say that Halfehide afterwards sold it to Andrew Grey, who owned it in 1590. A little more detail appears from another entry in the same work, where speaking of the manor of Moor Hall adjoining Barkesdon he says that Edward Halfehide purchased it about 1564, and in 1569 joined in 'a recovery to settle the same on his marriage with the daughter of Sir Edward Capell, of Aspenden, and conveyed the manor to Sir E. Capell and Gyles Capell, his son, as a jointure for his wife.; but that about two years after he sold it to one William Gurney. Not being concerned for Mistress Anne Halfehide's interests we need not stop to enquire into the questions raised by these statements. For our present purpose it is enough to note that Tannis is said to belong to Halfehide, that Sir E. Capell is said to be of Aspenden, and that the marriage took place in the year 1569. Of one of these facts we have confirmation in Sir E. Capell's will which is dated 21st January, 1571.2 In it he describes himself as of Aspenden, where he desires to be buried, and goes on to bequeath to his eldest son Henry "the hangings in my chamber at Tannes commonly called my Lady Katherine's chamber with the bed and furniture in the same chamber whole as it standeth and the bed and furniture whole as it standeth in the chamber over the Hall there at Tannes aforesaid." From this it appears that two years after the date both of the marriage and of the making of the inventory, Sir E. Capell was himself living at Tannis, and owned some of the furniture. One of the rooms named in the will, "the chamber over the Hall," occurs in the inventory, but there is no mention of the other; nor have I any suggestion to make as to who Lady Katherine may have been. A son, Gyles Capell, was perhaps also living at Tannis, if the room in the inventory named "Mr. Gyles' chamber" was so called from him; the only Katherine I know of was wife to Henry, legatee of the furniture, but she seems to have resided at Rayne, where she died the year after, 1572. There remains, of course, the possibility of a Katherine Halfehide, but as to this I have no information. I do not propose to deal here with the story of the Capells, but this much may be mentioned as suggesting a second connecting link with Tannis, in addition to that formed by the marriage of Sir E. Capell's daughter to Edward Halfehide. Owner of two estates not far distant, Rayne in Essex, and Hadham Hall in Herts, in one or other of which the family is found living between 1500 and 1678, William Capell, the founder of this branch of the family, had purchased in 1506 the manor of Walkern which lies close to Tannis; while nearer still is Cottered, where Sir Edward owned a "lease and term of years," which is by his will bequeathed to his son Gyles. These facts, combined with the marriage of his daughter, probably afford the explanation of our finding Sir Edward at Tannis rather than at either of his other seats. Added to this is the undoubted fact that Sir Edward was at this date very old. When he was born does not appear, but in 1491 there are accounts of moneys paid for his schooling, and given to him for pocketmoney: assume him to have been eight years old in 14-91, in 1569 he would have been eighty-five, an age at which a daughter's care may have been more than ever needful to the old man. The family problem must be left unsolved, and we can only deal with the document as we find it. It begins with the offices, and speaks first of the dairy or "mylke house," where are the usual appliances for butter and cheese making:

These dairy utensils are all obvious except, perhaps, the kymnels, which seem to have been shallow tubs in which the butter was washed and salted when fresh from the churn (see New Eng. Diet. s. v. Kimnel). Next follows the "sellar," in which were:

In the "buttry" which comes next we find much the same class of article:

The larder contains the usual assortment of "bourds," shelves, and tubbs, with two "mynsing," two chopping knives, and a cleaver. There is also here an "ambry," or cupboard, a word which now survives only in the form "aumbry," limited to ecclesiastical use; it is akin to the French "armoire." The boulting-house and the bake-house both have to do with the making of bread; the former being where the flour was pre pared and sifted through a bolting cloth, probably, I suggest, stretched over the "lynnen wheeles" which we find among the items. Though not dealing here with etymology I cannot help lingering for a moment over this word boulting, as it gives us a key to two words with which few would suspect it to be connected: it comes from the cloth which was used to sift the flour; and can be traced back through a Low Latin word "burra," to the Greek 'πνρ, the cloth taking its name from its reddish, or fire colour. Far back this cloth was employed for various uses, from two of which we get the "biretta," worn by the priest, and the "beret" worn by the Pyrennean peasant to this day. The boulting-house contained:

while the bake-house added

the last being the flat long-headed shovel used for taking the bread out of the oven. Though lost in English it survives in modern French as the usual name for a spade. The farming stock is given under the heading "The Bayly of husbondry, Wortham," (no doubt the bailiff's name) and includes

Wright's" Dialect Dictionary" explains a mullen halter as the bridle of a cart horse, but offers no suggestion as to the origin of the word, nor can I find any explanation elsewhere. Of the other articles a skep is a word still in use for a wide open basket, while a bushbrake I take to have been a form of harrow. Before passing on to the rooms themselves we may perhaps take the pewter, plate, and linen, all of which are set out separately. The latter appears under the heading "the napery wth. Mother Wigg," who must have had charge of it.

The modern house-wife would find it difficult to recognize the contents of her linen-press in the foregoing: yet, with a little explanation they are the same. Pillow-bere is the old name for pillow case, while the finer and coarser qualities of sheets and towels are flaxon and towen respectively, tow being the refuse from the finer material flax. Diop is our modern diaper, a word in much commoner use, as the name of a material, in old days than now. Its derivation is very doubtful, but examples will be found in the "New English Dictionary" of various spellings, one of which (dyoper) comes very near to ours. It is curious, considering that the baking of clay is one of the earliest arts of civilization, how little earthenware vessels were used for domestic purposes in early times, wood and pewter filling the place. Pewter, a compound of lead and zinc (the word itself a form of "spelter") was the common material in household use. Of this Tannis possessed:

The list of silver plate is much the same as would have been found in most houses of this style and date: in reproducing it one cannot help thinking what it would mean if it appeared in a sale catalogue of to-day.

We now come to the house, and begin with the kitchen, where the utensils were as simple as were probably the results they produced, boiled or roast being the only alternatives.

All these are too obvious to need much explanation, except perhaps to say that a posnet is a small pot, a scomer a skimmer, while the racks were used to hang the spits on for roasting. Pot-hooks and pot-hangers have now an educational meaning, but were then used to suspend the pots from the "cremaillere," a thing common enough in England, for which I can, however, find no English equivalent. A distinction seems to be drawn between them, and perhaps the pot-hook was the "cremaillere" and the hanger the hook by which the pot was hung on it. Only two sitting-rooms seem to have existed, the entry, and the parlour. The former I take to have been the hall, which at this date was ceasing to be used as the main living room of the house. Its furniture was simple, though we must remember that we are dealing with movable furniture only, and not with fixtures; it contained, One longe table standing up agaynst the wall, a wycker skryne and a dexte. the latter article seems an odd word, but Halliwell gives "dexe" as a form, and its meaning desk, is obvious from a later entry under Mistress Anne's chamber. The parlour was evidently the main living and, teste the toasting fork, eating room of the house. Its furniture consisted in

First one notices the economy, not unknown of modern paperhangers, of keeping the old hangings under the new: and next the loyalty which provided a framed picture of the Queen, for I think that "table" means frame, rather than that the picture was painted, as no doubt it was, on board; in support of this I may refer to the "pictures on bourds" which occur lower down. The materials employed for decoration were as various as to us they seem curious, so much have the words been either absolutely lost, or changed their meaning and use. Say, a kind of thin woollen, or serge, is of the former class, while buck ram and fustian are no longer used for curtains. Fustian apes is a curious example of the degradation of a word: the material was a cotton velvet, taking its name, perhaps, from the fact that it was originally made at Fostat, a suburb of Cairo: in later days Naples was famous for it, whence it came to be known as fustian of Naples: this by an easy process of degradation became fustian anapes, and so down to our fustian apes. In both the "New English Dictionary" and the "Draper's Dictionary" will be found many examples of the gradual process of decay. Quoysshion, though an odd spelling, is a usual one, and carries one back a little nearer to the origin of the word, for a cushion was first used to support the hip (coxa) on the triclinium. A cobyron I take to have been a more artistic form of andiron, ornamented with a knop at its end. There were fourteen bedrooms, called by the following names:

they contained twenty-one beds, but only three had fireplaces. The best furnished was that of Mistress Anne, the lady of the house, which contained:

Another room, not so fully furnished, though with greater magnificence, was the chamber over the parlour; in it we find:

"Braunched" silk was probably embroidered with spriggs, and "chaungeable" is, perhaps, the equivalent of the modern "shot." Our notion of a carpet is that it lies on the floor, but here it is equally applied to something covering a cupboard. As these lines are written I notice an apt confirmation of this old use. In a case recently before some ecclesiastical court, relating to the proper covering for the Communion table, the canons of 1604 were quoted, ordinances yet in force. The eighty-second of these directs that "the Table be covered in Divine service with a carpet of silk or other decent stuff thought meet by the Ordinary, and at the time of the Ministration with a fair linen cloth as becometh that Table." The number of cupboards in the house is surprising, many of them "livery cubberds": these were originally used for storing the rations of food issued for the day, but the word early came to mean a cupboard of any kind, more especially an ornamental cup board or sideboard. A quotation of 1571, given in the "New English Dictionary" (s. v. "livery") is exactly in point, as it speaks of "a carpet for a livery cupboard." Caddys is a word now quite lost, but Halliwell knows it as worsted, or worsted ribbon, the former perfectly suiting its use here. The beds were of two kinds, trussing and trendle: Halliwell defines the former as a travelling bed, an explanation which the word itself seems to support: but here it is obviously of a more permanent nature, as it is always fitted with a tester, and curtains: while the trendle bed seems to have been of a movable character, what would now be called a truckle bed. The contents of the chamber over the hall, as being the room dealt with in Sir E. Capell's will, may also be given in full:

The meaning of the word mantel has, in modern times, been so much narrowed that we are puzzled to account for it as part of the furniture of a room. At this date it meant a covering, probably for a bed, for in a similar inventory of 1622 I find "a redd mantell to laye upon a bedd." The furniture of the remaining bedrooms was much the same, and need not therefore be given in detail; it offers however two materials which have not occurred before dornix, a coarse sort of damask, taking its name from Tournai, which had a reputation for making it; and sowtage or sowltage, for the word comes under both spellings, of which Halliwell tells us that it was a coarse cloth or bagging, which suits its use here, for the hangings are described as being of "paynted sowtage." Last in the list comes the armoury, proof that the days of self-defence were not yet passed, this contained:

Skeat defines a jack as a coat of mail; the skulls were doubtless headpieces, and the "capps" worn under them to make them easier. ----- 1 Burke, Gen. Arm. notes the grant in 1560 to Halfehide of arg. two chevrons conjoined in fesse, sa.: Crest, a greyhound sejant, or, collared, sa.; but makes no mention of the roses. 2 The will will be found at 34- Daughtry: P.C.C. He died in 1577, but in the registers of Aspenden there is no trace of his burial there, nor am I able to say where he was buried. 3 "Her pink'd porringer fell off her head" - Shakespeare: Hen VIII, v. 3. |

This house, photographed circa 1900, is probably what remains of the Tannis described in the Inventory

For information on Tannis Court Farm see OVERELL, Aspenden, 19th/20th century