|

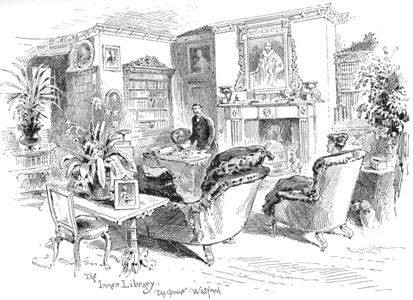

The Grove, Watford

|

|

The Grove, in its time, was one of the most fashionable homes in the country. Invitations to weekend parties at The Grove were highly sought after and prized. In the days of the 4th Earl, (George William Frederick Villiers 1800 - 70), Saturday to Monday visiting became fashionable. Guests would drive down from London on Saturday, and return on Monday. Sometimes, the Clarendon's would drive down from London unexpectedly, in the evening. A bedroom on the ground floor was kept in readiness for them. On one of these occasions they had just gone to bed, when the french windows opened, and a stablehand crept stealthily into the room. On seeing two figures in the bed, he asked, "on which of you two darlings shall I begin?". With perfect composure, the Earl replied, "I pray Sir that I, at any rate, may be spared your, no doubt, well-meant, but most unwelcome intentions". In those days many of the guests would bring their own servants with them. At times there would be many ladies maids and valets in residence. In the late 19th Century the domestic staff at The Grove was very large. Many of them were kept in the background and never seen. For instance, two men were employed solely to keep the colza oil lamps filled and trimmed, there being no gas or electricity on the estate at that time. Incidentally, there is still no gas laid on. The 'visible' staff included a Butler, and the Earl's personal valet, a Mr. Drowley, who was groom of the chambers, and who was in the employ of the Clarendons from the age of 15 until he was 75. One of his jobs was to see that all the bedrooms and living rooms were well supplied with writing paper. It was of a type seldom seen today, very thick cream coloured paper, stamped with the address in one corner, and the Earls crest in the other. Both were in light blue. He also kept up the supply of other writing requisites, pen holders and nibs, pencils and rubbers. What other duties he performed is unknown. Also on the staff, and very much in view, were four 'figure footmen'. These were so called because their duties consisted of little else than being there! They were dressed in claret coloured coats, dove grey waistcoats, plush knee breeches, and shoes with gold buckles. The kitchen had at least four kitchen or scullery maids. These were under the orders of the French chef, Monsieur Thevenot, and his successor, Monsieur Menessier. As with all chefs and cooks, they each had their own specialities. Thevenot, was famous for his 'Homard Thevenot', which consisted of small pieces of hot lobster cooked in bouillon (a thin stock), and covered with a mixture of egg yolks, liqueur brandy, cream, Madeira and herbs. Also famous, was Menessier's 'Macedoine Faisan', which was cuts from pheasants breasts which had been immersed in a creamy yellow sauce, the basis of which was mushrooms and truffles. By the 1920's the kitchen was ruled by a cook, one Maggie Jones. She is remembered by Fred Ward, who worked in the gardens at that time. He also made reference to Mr. Drowley, who had by then become the butler. Other staff mentioned by Fred Ward included a Mr. Pritchard, who was the gatekeeper, and lived at the lodge on the Hempstead Road entrance. Another was George Ricketts, the cowman, who looked after the small dairy herd. He was assisted by a young dairy maid. George worked from 6 a.m. until well after the afternoon milking, seven days a week! For this he was paid 30 shillings per week, free board, milk and firewood! He was also allowed a small plot of land on which he could grow vegetables. George's brother, Alfred, was the estate horseman and carter, performing other duties besides. These included cleaning out the muck from the cowsheds, and making manure for the garden! Another man with many jobs was Len Hart, the estate carpenter, who also acted as general handyman. The gardens at The Grove were among the finest in the land. There was a walled garden, which was divided into four sections, each of which was well over an acre. Along the length of one wall ran the greenhouses. In these were grown peaches, grapes, nectarines and figs. All grew under the watchful eye of Charlie Woods, son of the head gardener.

Servants would dress, to a certain extent, according to the dictates of fashion, very often in the same style as their employers. Two opposing factors, however, dictated the way that the servants were dressed. One was the need for economy and the other a desire on the part of the master to display his wealth on the backs of his liveried staff. Knee breeches began to be replaced by trousers at the beginning of the 19th Century, but the servants kept to the old style of breeches. Powdered wigs lingered in to the 19th Century, and were then replaced by powdered hair. One footman of the time remembers being paid £2 per year for Violet Powder. Trousers for footmen came in in the 1870's. These were worn with a tailcoat and a waistcoat (striped horizontal for indoor servants, and vertical for outdoor). By the late 1880's a head footman could be distinguished by his long overcoat. Coachmen and grooms would wear much the same uniform as a footman, with the waistcoat stripes going the opposite way. In the 20th Century the coachman became a chauffeur, who still wore riding breeches. This stayed the uniform for the next twenty or so years. Both the coachmen and chauffeurs wore black leather gaiters. The page was the most changed member of the servant class. During the time of extensive overseas trade and travel many households employed Negro pages, who wore silver collars engraved with their employers name. By the reign of Queen Victoria this practice had lessened. From the mid 19th Century his uniform consisted of a short tight coat, like an Eton jacket, and pantaloons or long trousers. The practice of having rows of small buttons, all down the coat usually earned the page the nickname, "Buttons". Housemaids dress usually followed the broad dictates of fashion, but also depended to a certain extend on her duties, employers residence and status. Where a footman was employed the housemaid was very much in the background. The custom of changing uniforms for the afternoon continued well into the 20th Century. Houses where there were children would have, in addition to a Nanny, one or two nursery maids. As in 'Society' there was a class system among servants. Their standing in this hierarchy depended on their position and whether they were indoor, outdoor, upper or lower servants. The protocol "below stairs" was far stricter than might have been imagined.

|

|

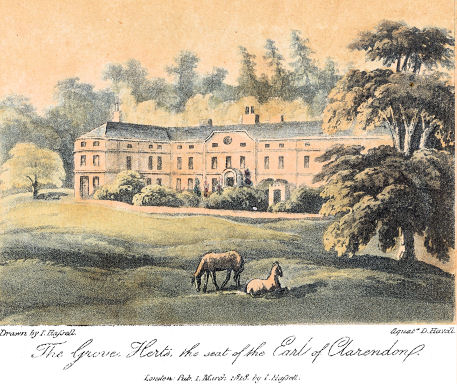

The Grove, Herts, the seat of the Earls of Clarendon

Drawn by I. Hassell Aquatint by D. Hassell London Pub 1 March 1818 by I Hassell

Probably from |

|

|

King Edward VII visits Watford and stays at The Grove in July 1909. Postcards by Downer |

The Earl of Clarendon moved out in 1922 but retained the property for a few years. During this period it had various uses, possibly at the same time. This includes being a high class girls boarding school and also the "National Institute of Nutrition and College of Dietetics." The Grove was then purchased by The Equity & Law Life Assurance Company. They sold it to the LMS Railway company in 1939, which used it as its headquarters during the war. When the railways were nationalised in 1948 it passed first to the British Transport Commission, and later to British Rail, when it was used as a training centre. More recently it has become a country hotel and golf course.

| See Grove School, Watford, 1925-1929 (word document) |

|

Grove Mill Lane, Watford

|

|

|

|

|

|

Canal, Grove Mill Lane, Watford |

|

Life at The Grove

Life at The Grove